Here’s what Colorado’s gray wolves are up to as they establish territories across the Western Slope

With 25 wolves released, four packs formed and 10 deaths, the build toward a self-sustaining population of the species is underway

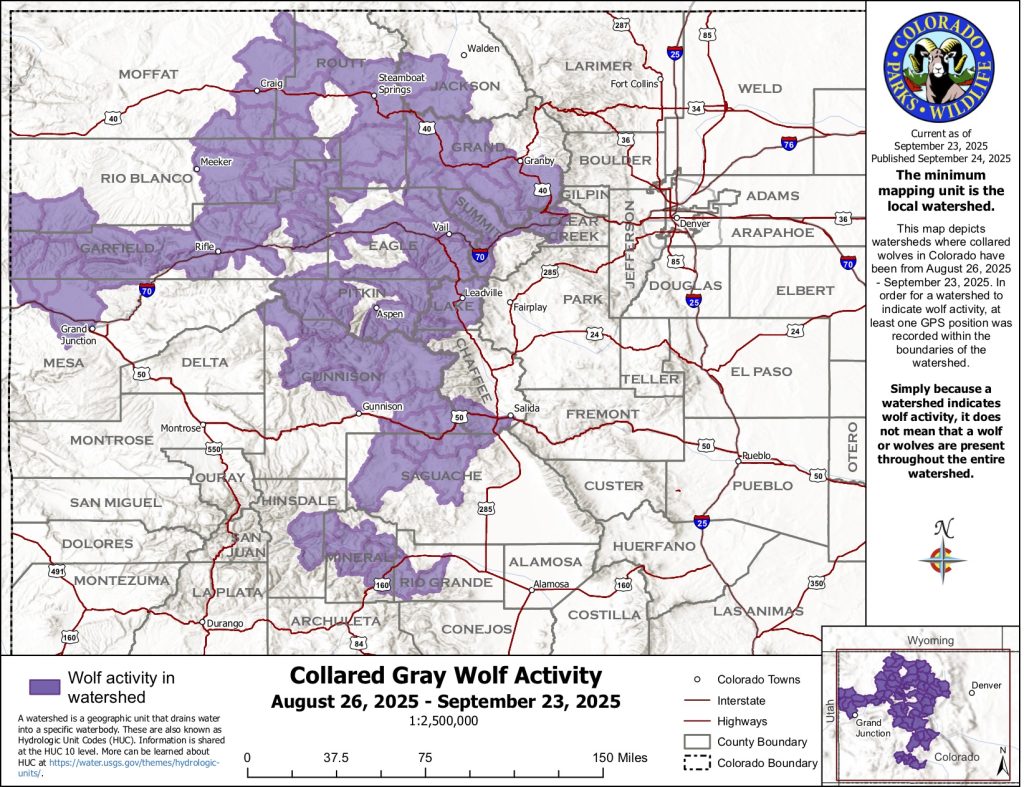

Colorado Parks and Wildlife/Courtesy Photo

Earlier this year, one of Colorado’s translocated female gray wolves was making broad movements across the Western Slope. Then, one day, she stopped exploring on a wide scale and settled into an area with high-quality wolf habitat — abundant prey, away from high volumes of human activity.

It was there that a male wolf found her, either by following her scent or just by chance. The two mated and became a pack.

The story exemplifies the two types of movement patterns that Colorado Parks and Wildlife is observing as it aims to build Colorado’s self-sustaining population of gray wolves — a mandate handed down to the agency by voters in 2020.

“The biggest things, as far as movement, we’re seeing right now are just the difference between territorial wolves and dispersers,” said Brenna Cassidy, Parks and Wildlife’s wolf monitoring and data coordinator. “Wolves are social; they live in these groups and they defend a territory. When that happens, their movements look really different than the exploratory, dispersing individuals.”

Dispersing wolves

Colorado is almost two years into its reintroduction of gray wolves. Since December 2023, 25 wolves have been relocated to the state, 10 have died and four packs have formed. Per its wolf plan, Parks and Wildlife is targeting the release of 30 to 50 wolves in three to five years. This winter, the third release of between 10 to 15 animals could be the state’s last.

When wolves are first relocated to Colorado — with the first 10 coming from Oregon and the next 15 from British Columbia — they automatically take on the role of what Cassidy refers to as a “disperser.”

A disperser, she said, is a wolf that leaves the pack and territory it was born in to “go off and make it on their own.”

“Even though it was like human-mediated (the translocation from their home pack) triggered that exploratory movement to try and find a mate, try and find a pack for that chance to reproduce.”

Right now, Colorado has a higher proportion of these dispersers than what you see in more established wolf populations. So, while the proportion is expected to decline, these types of explorers will always be present in the growing state’s wolf population.

“The proportion of (dispersers in) the population is higher at this point because they just need a chance to find each other on such a large landscape,” Cassidy said.

Typically, in established populations of wolves, while it ultimately depends on the individual wolf, most dispersal occurs when the animals are between 1 and 3 years old. Both males and females will leave their pack. However, in some populations, the proportion of males that leave is higher, Cassidy said.

“Something we see pretty commonly is that a wolf that is about to leave its home pack and disperse might do an exploratory movement and then come back to their pack, stay a little bit, do another movement, come back,” Cassidy said. “Eventually, they just won’t come back, and they’ll just keep moving whether they find a mate or not.”

Where they go and whether they come back depends on a couple of factors.

“It’s really dependent on the time of year that wolf is leaving, where they started, where all the other wolves are in the area,” Cassidy said. “Also, just because a wolf meets another wolf of the opposite sex doesn’t mean that they want to pair with them. They definitely have the choice to make of whether they stay with that wolf or not.”

Cassidy added that “wolves are really, really good at avoiding inbreeding,” and one of the ways they’ve evolved to avoid it is through dispersal.

Different dispersal strategies depend on the individual. Some wolves might take their time exploring an area before moving on to another to evaluate that area for a few weeks. Others might move more quickly, constantly exploring without stopping for extended periods of time.

Cassidy said how the exploratory wolves are moving is unpredictable but unsurprising.

“While it’s not necessarily predictable where a wolf decides to explore, where a wolf doesn’t decide to explore, or the speed at which they’re doing that, it’s not necessarily surprising what we’re actually seeing,” she said.

Building territories

Ultimately, these dispersing wolves are aiming to settle down in a pack. Once packs form, the wolves’ movement patterns change as well.

“While we can’t say that wolf movement on a really fine scale is necessarily super predictable, those territorial wolves are more predictable in that they’re much more likely to be in their polygon than they are to be outside of it,” Cassidy said.

It’s something that Colorado saw start to happen a little more this year. In the spring, Parks and Wildlife confirmed that there were four packs in the state:

- The Copper Creek pack, which originally formed in Grand County in 2024, with five pups born. After spending five months in captivity with four of the pups, the matriarch had a second den this spring in Pitkin County when she mated with a British Columbia wolf released this January.

- The King Mountain Pack in Routt County, which has at least four pups

- The One Ear Pack in western Jackson County, which has at least six pups

- The Three Creeks Pack in Rio Blanco County, which has an unknown number of pups

While the boundaries of a pack’s territory might shift slightly year to year — due to habitat changes like wildfires, floods or changes in the activity of deer and elk herds — these territories typically stay in the pack for generations.

“As long as there is a pack in that territory, it’ll be passed down,” Cassidy said. “Those territories, whether or not they blink out, are mostly tied to is that pack persisting? Are there wolves in that pack that are going to keep defending that territory? Because if a pack totally dissolves — there’s a high mortality one year, and there’s just one or two left, and maybe they’re related to each other — they might go off and disperse and try and find mates and kind of abandon that territory.”

The den site — where the pups are born and spend the first months of their life — typically serves as the “core” of the territory, Cassidy said.

“It’s kind of like their home base for part of the year, and you can only travel so far away from a den and then come back,” she said, adding that where the den is can also shift from year to year, but often does not.

“The pack may stay at the den throughout the summer or may leave the den and localize at a rendezvous site,” Cassidy said. “The den or rendezvous site is the focus of the pack’s social activities for the summer months and is usually a protected area near water.”

As Colorado’s wolf restoration continues with the expected release of 10 to 15 wolves in southwest Colorado this winter, Cassidy expects to see fairly similar movement patterns over the next year.

“We can anticipate more territories forming just because there’s a higher chance of them running into each other,” she said. “I would expect that pack formations will keep happening. They’ll kind of fill in areas. It’s common for territories to neighbor each other and maybe even overlap a little bit.”

This also means new pups will likely be born in the spring.

“In the further future, after translocations, when more wolves will be reproducing in Colorado, we’ll see those pups grow up in those packs, and then they will naturally disperse,” Cassidy said. “As long as we have packs and wolves, we will have dispersers. But the proportion will kind of settle out into a lower number than what’s there now.”

Support Local Journalism

Support Local Journalism

Readers around Glenwood Springs and Garfield County make the Post Independent’s work possible. Your financial contribution supports our efforts to deliver quality, locally relevant journalism.

Now more than ever, your support is critical to help us keep our community informed about the evolving coronavirus pandemic and the impact it is having locally. Every contribution, however large or small, will make a difference.

Each donation will be used exclusively for the development and creation of increased news coverage.