Colorado River states fail to meet federal negotiations deadline

The federal government will now impose its own plan as drought worsens across the basin and the threat of litigation looms

Chris Dillmann/Vail Daily

The seven Colorado River states were unable to agree on how to manage the river and its major reservoirs by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s Feb. 14 deadline.

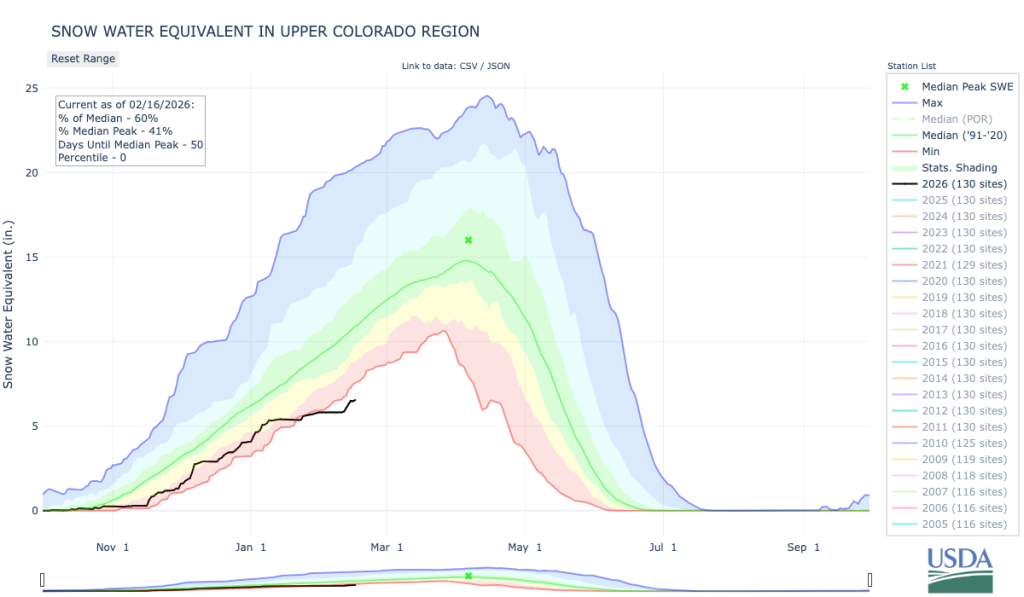

This marks the second missed federal deadline in more than two years of high-stakes negotiations between the upper and lower basin states over the post-2026 operations of Lake Powell and Lake Mead. At the same time, drought conditions have worsened across the basin, amplified by a historically low snowpack in the West and critically low levels forecast for the reservoirs this spring.

Interior Secretary Doug Burgum said that without a seven-state consensus, the U.S. Department of the Interior, which oversees the Bureau of Reclamation, will step in and finalize its own plan that attempts to meet the needs of all seven states by Oct. 1.

“Negotiation efforts have been productive; we have listened to every state’s perspective and have narrowed the discussion by identifying key elements and issues necessary for an agreement,” Burgum said in a statement on Saturday. “We believe that a fair compromise with shared responsibility remains within reach.”

The Bureau of Reclamation, which operates the two reservoirs, has been undergoing the National Environmental Policy Act process in tandem with the states’ negotiations to ensure any agreement is finalized by this fall. It released a draft menu of options in January, with its public comment period open until March 2.

Allocation of the Colorado River’s water supply is driven by a 1922 compact agreement, which divided the river into an upper and lower basin. While the Upper Basin states — Colorado, Utah, Wyoming and New Mexico — rely predominantly on snowpack for their water supply, the Lower Basin states — Arizona, California and Nevada — rely on releases from Lake Powell and Lake Mead.

For the last two years, the seven states have been negotiating new operational guidelines to govern the two Colorado River reservoirs. The current guidelines were set in 2007 and will expire this year. Originally granted a November deadline, the federal government pushed the deadline for a seven-state consensus to February.

The agreement will govern how the Bureau operates Lake Powell and Lake Mead, particularly under low reservoir conditions; allocates, reduces or increases annual allocations for consumptive use of water from Lake Mead to the lower basin states; stores and delivers water that has been saved through conservation efforts; manages and delivers surplus water; manages activities and makes cuts above Lake Powell; and more.

Disagreements continue up until deadline

One of the main disagreements throughout negotiations has been who should be making cuts to water use. The Lower Basin states have advocated for basin-wide water use reductions. The Upper Basin states, however, have pushed back on the idea, claiming they already face natural water shortages driven primarily by the ups and downs of snowpack.

By Friday, it seemed imminent that no consensus would be reached, and both the upper and lower division states dug in their heels on these arguments.

A statement from the Lower Basin state governors on Friday focused on the cuts their states have brought to the table — Arizona offering a 27% cut of its Colorado River allocation, California 10% and Nevada nearly 17% — and asking the same from the upper basin states.

“Our stance remains firm and fair: all seven basin states must share in the responsibility of conservation,” the governors’ statement read. “Our shared success hinges on compromise, and we have offered significant flexibility, allowing states without robust conservation programs time to gradually develop these programs in ways that work in each state.”

However, the upper basin states continued to push that the allocations and cuts must be based on the supply of the river. In a statement, the Upper Basin states said that this winter’s critically low snowpack will already “amount to reductions greater than 40% of the proven water rights” across the four states.

“We’re being asked to solve a problem we didn’t create with water we don’t have,” said Becky Mitchell, Colorado’s water commissioner and lead negotiator in the post-2026 operations. “The Upper Division’s approach is aligned with hydrologic reality and we’re ready to move forward.”

“This year is a stark reminder of why all in the Colorado River Basin must learn to live within the available supply, as water users across the Upper Basin are preparing for deep cuts to their water supplies,” said the Upper Colorado River Commission in its statement.

In negotiations, the Upper Basin states said they have “consistently offered compromises to develop a supply-driven operational framework as a practical and realistic path forward” and proposed “serious, implementable solutions grounded in today’s hydrology.”

A statement from the Upper Basin governors on Friday said that their four states offered up every tool available, including “releases from our upstream reservoirs, a robust contribution program, meaningful voluntary conservation and continued strict self-regulation of water supplies.”

Stakes rise as water levels fall

The operations of Lake Powell and Lake Mead have widespread implications for the approximately 40 million people, seven states, two countries and 30 tribal nations that rely on the river. In Colorado, the Colorado River and its tributaries provide water to around 60% of the state’s population.

An uncertain climate future and this year’s extremely dry winter have only heightened concerns about the two reservoirs’ operations.

The Bureau released its latest spring forecast for the basin on Friday. Following a much drier than normal January, Lake Powell’s inflow is expected to decline significantly, dropping the reservoir below the level necessary to produce hydropower by December and to the lowest elevation on record by March 2027.

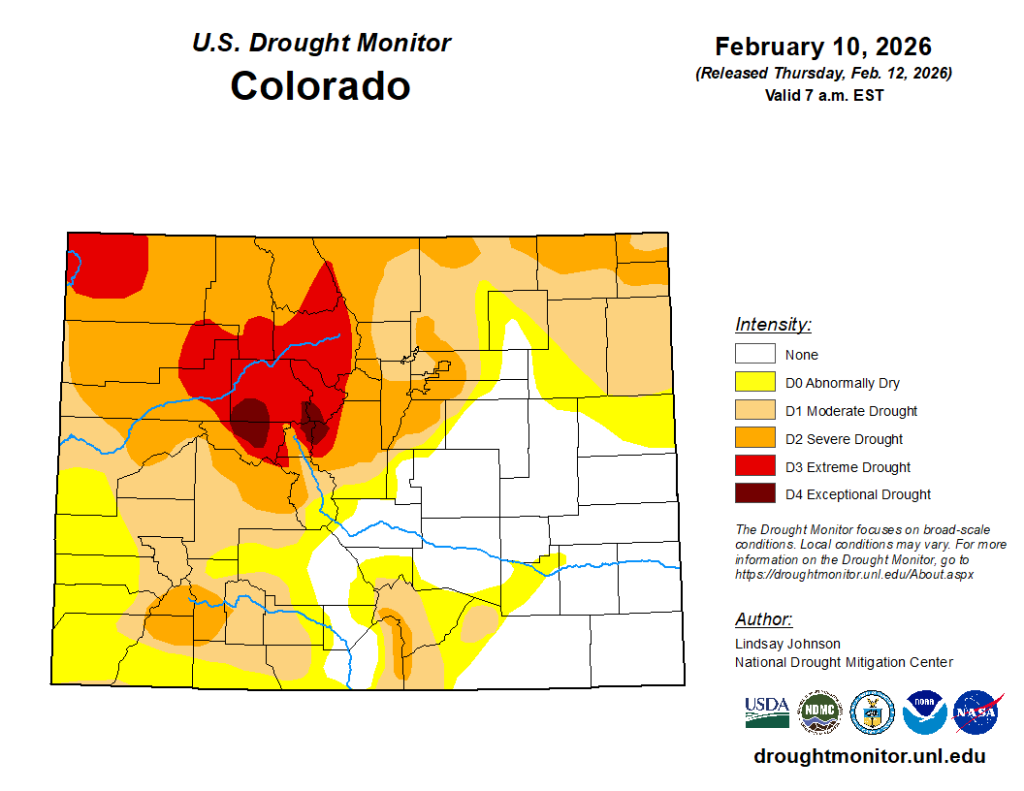

As Colorado experiences its worst snowpack in the last 30 years, drought conditions have worsened across the Western Slope. The latest Colorado Drought Monitor from the U.S. Department of Agriculture shows exceptional and extreme drought developing across the north-central mountain region. Snowpack within the Colorado River headwaters sits at 55% of normal as of Feb. 16.

A statement from a coalition of conservation and sportsmen groups on Friday said the states’ “continued gridlock carries real consequences for the river and those who depend on it.”

The coalition included American Rivers, Environmental Defense Fund, The Nature Conservancy, Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership, Trout Unlimited and Western Resource Advocates.

“The system is operating with little margin for delay,” the statement reads. “Basin snowpack is at record lows, storage at Lakes Powell and Mead remains precarious, and hotter, drier conditions that present increased wildfire risks, water quality concerns, and water supply restrictions and shortages are now the operating reality.”

A threat of litigation looms

Without a consensus, concerns of litigation have been swirling, carrying with them concerns that taking the matter to court would delay progress toward addressing the climate challenges facing the basin.

“Litigation won’t solve the problem of this long-term aridification,” said Colorado Sen. John Hickenlooper in a statement. “No one knows for sure how the courts could decide and the math will only get worse. We need to avoid wasting time — and water — and come together to chart a path to a more sustainable future.”

With the deadline for consensus past, the new word from all parties is collaboration as they attempt to skirt around the threat of litigation.

Burgum said that the Interior Department remained dedicated to working with the seven states “to identify shared solutions and reduce litigation risk.”

“Conflict won’t change the hydrology,” said Brandon Gebhart, Wyoming’s water commissioner, adding that the upper basin was “choosing workable solutions over litigation and political messaging.”

The Lower Basin governors said in a statement that they remain “unwavering” in their commitment to a collaborative outcome.

“We will continue to pursue a negotiated resolution while protecting our water users,” they added.

While Colorado and the Upper Colorado River Commission have also expressed commitment to collaborating and providing comments to the Bureau’s draft environmental impact statement, Colorado Attorney General Phil Weiser said in a statement on Friday that “Colorado is prepared for any litigation, and we will work tirelessly to protect our state’s rights and interests under the Law of the Colorado River.”

Support Local Journalism

Support Local Journalism

Readers around Glenwood Springs and Garfield County make the Post Independent’s work possible. Your financial contribution supports our efforts to deliver quality, locally relevant journalism.

Now more than ever, your support is critical to help us keep our community informed about the evolving coronavirus pandemic and the impact it is having locally. Every contribution, however large or small, will make a difference.

Each donation will be used exclusively for the development and creation of increased news coverage.