A river of worry through Garfield County as drought worsens

Post Independent archive

The Colorado River is the lifeblood of over 30 million people.

Whether its potable water, agricultural needs, or recreation, seven different states between Colorado and the Pacific Ocean actively rely on the water that flows through Garfield County.

Yet with consistently increasing yearly temperatures, decreasing yearly snowpacks, and constant threat of wildfires — the health of the legendary watershed has never been more important. The Colorado, Roaring Fork, Crystal, and Frying Pan Rivers all have individual and unique impacts that stretch from the local economy to produce and amenities.

Brendon Langenhuizen, the Director of Technical Advocacy for the Colorado River Water Conservation District explained the importance of conservation and the difference that working for your neighborhood can make on the communities health.

“One person not watering their lawn once won’t make a difference to the amount an irrigator in Grand Valley can use, but it will make a difference in the stream right outside your house,” he explained. “That’s 15 gallons per minute that can flow in the rivers, and continue to keep the water cool. It’s really important to listen to whatever your water providers are saying about restrictions and try as hard as possible to abide by them.”

“Spreading the available supplies as much as possible is the biggest thing at play. If enough people are on board and working for the same goal, that’s when we can see some changes for the irrigators in Grand Valley,” Langenhuizen continued.

Flows

Following a “mixed” winter resulting in the lowest snowpack seen in 10 years, it was not unexpected that riverflows would fail to hit an 80-year median this summer season. But a dramatically dry summer took a bad situation and made it worse.

In 2025, the Colorado River peaked barely above 4,000 Cubic Feet per Second (CFS), measured by the United States Geological Survey near Dotsero. The 4,120 CFS peak on June 3 fell far short of the median of 6,200 CFS (1940-2025).

Langenhuizen said he was more concerned about the near-nonexistent monsoonal season this summer — and its implications for what future monsoon seasons could look like.

“The monsoons just aren’t really coming in like they were forecasted to three months ago,” he said.

He explained that the supplement of heavy rains in the higher alpine can both briefly reinvigorate the tributaries and provide much needed assistance to the ranching community.

“(The peak) means that it’s just a drier year,” Langenhuizen said. “I think that not getting those monsoons — which haven’t shown up yet — is really what has put us into this situation. We had average snowfall to lower yield, which put us into this dry category of year, and we haven’t had those monsoons that bolster those flows later throughout the late summer months.”

The Roaring Fork River isn’t having the same issues as the Colorado River, but the sharp and sudden descent of CFS since mid-June has put further stress downstream on the 100 year old Cameo Call in Mesa County.

The Cameo Call has been providing water throughout the Grand Mesa area for over a century — much of which is thanks to the commonly dense snowpack running down the Crystal and Frying Pan Rivers, eventually rushing through the Roaring Fork and into the Colorado.

The runoff yield in the spring was subpar, which contributed to an up-and-down increase in CFS during April and May, supplemented by releases from Ruedi Reservoir. On May 14, the Roaring Fork had 1,500 CFS in the river, but just one week later, on May 21, the river was only running at 673 CFS.

“The Roaring Fork normally provides a lot of water for the Cameo call, but because the Fork was so low this year, it wasn’t producing much. The Cameo Call came on a little bit sooner than normal, but with it being a dry year — it wasn’t that unexpected or irregular,” Langenhuizen said.

The Roaring Fork River peaked at 3,190 CFS on June 3, measured in Glenwood Springs. According to the USGS, the peak came around two weeks early, and was over 1,000 CFS lower than the average.

Potable water

Although the flows aren’t performing as hoped, there is no shortage of clean water throughout Garfield County. Contrarily, the subpar flows and runoff during spring has quietly made the jobs of water treatment plant workers easier.

According to Sara Flores, the Silt Water Treatment Plant Operator, the flow levels haven’t come close to reaching a point of concern for her — and even explained when the water is warmer and flowing with less sediment, the easier treatment becomes.

“Our river inlet has about 3 feet in it, which isn’t actually too bad,” she said. “I might be concerned if it starts to drop near 1 foot — but at that point there are steps we can take like cleaning the sediment out of our inlet or combining our inlet with our wells.”

“As far as the quality of water coming in, it’s been a lot easier for me to treat,” Flores continued. “This summer has been sort of a mixed blessing for us. The warm water is easier for us to filter, because it’s not as dense and we also haven’t been having to deal with the turbidity that normally comes with monsoons.”

She explained that the plant was treating on average over 400,000 gallons of water per day, and her concerns lied elsewhere — with the agricultural community.

“As far as potable water goes, we are in a good spot,” she said. “People tend to use less water when it rains, but right now, our average per day is about 430,000 which is pretty high for us, but the warm and less dense water is enabling us to keep up with that.”

Drought and fires

The 2025 summer on the Western Slope has been littered with extreme heat mixed with dry weather and powerful winds, resulting in fires all throughout the state — a point further stressed by the Lee Fire, which grew to become the fifth largest fire in Colorado State history.

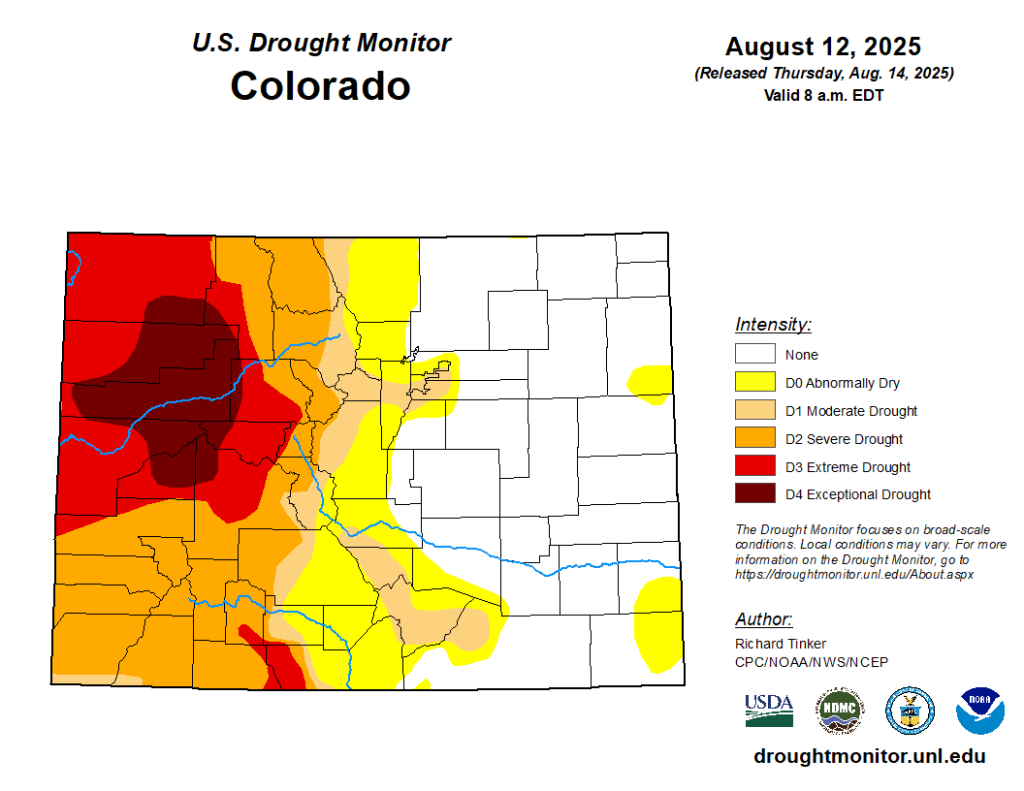

Drought conditions during the summer months are a regularity throughout the Western Slope. The Western Slope has seen at least one county in extreme drought conditions since April 22, and the State of Colorado hasn’t been 100% drought free since the summer of 2023, the U.S. Drought Monitor shows.

The lack of monsoon season has been the crux of the issues on the Western Slope, and the visual representation provided by the U.S. Drought Monitor shows the dire reality of the situation.

As the smoke begins to clear from the devastating Lee and Elk fires in Rio Blanco County, the Western Slope ecosystem is struggling to heal. Nearly all of Garfield County is facing “Exceptional Drought“, with areas in Rio Blanco and Eagle counties also experiencing similar conditions.

According to officials throughout the county, the communities at biggest risk from the low flows and exceptional drought situations are the ones who depend heaviest on the resources — the ranching community.

“It’s really dry and very hot, which means their crops need more water, and that water just isn’t there to the extent they want it to be,” Langenhuizen explained. “I think you’re starting to see some agricultural producers get a little stressed. They’ve been having to curtail water, even though they don’t have the full allotment of water coming in. There’s such a high demand for their crops that they need more water than they can actually get.”

“They’re actually having to share some of their water rights, which is unique, I don’t think that’s always the case this early,” he continued.

Farming

Although lawmakers and water officials are always fighting for their representatives and districts, that doesn’t mean they always agree on how to best use water — disagreements which could increase if available water supplies diminish significantly. The further down stream you travel, the less water and more problems you will find — a scary thought when the farming and agriculture communities reside in flatter and drier lands.

John Kuersten, a fourth generation farmer in New Castle, knows the importance of the issues, and explained how serious the agriculture community takes conserving water when their lives can flip upside down if they don’t have all the water they need — though explained that there aren’t many options in some situations.

“Water rights are a very tough topic, they are very complex and have a lot of history intertwined in them,” Kuersten said. “Most of the ranchers know what they have, know what they own, and who can use what. There are certain ditches that they know will be shut off at one point in the year. The ranchers know that and they plan for it. They expect it and know that in dry years, they are going to lose their water and there isn’t much to do about it.”

He continued to explain that the community has been making strides to reduce their usage with creative ways to irrigate their land, like the amount of water that can be saved by switching systems from flood irrigation to sprinklers.

“Most of the ranching community is in tune with trying to conserve water. There is a big push for conservation, and a lot of the ranchers have gone into conservation efforts trying to get their ranches under irrigated sprinkler systems rather than flood irrigation. I actually just received a small grant from the NRCS (National Resources Conservation Service) to fully convert one of my properties into fully sprinkled systems, and I have cut my usage in half.”

Kuersten explained that although the community has been making leaps and bounds to try and conserve every ounce of water, dilapidated infrastructure in some spots are contributing to spillage.

“The biggest issue we are facing right now is a lot of our infrastructure — especially in Garfield County — is aging and isn’t super efficient. They have a high seepage loss and there isn’t a lot of money out there for ranchers to convert their systems to sprinklers so that is a big holdup.”

Fishing

With so much of the local economy reliant on tourism and recreation, being able to bring in hundreds of millions of tourism dollars through a summer where Garfield County experienced exceptional drought is a place locals can hang their hats.

Dustin Harcourt, owner of a local fly fishing guide company — Harcourt Fly Fishing 3G, has lived and breathed the Colorado River since he began guiding in 1993. He created his business in 2014, and has set up his livelihood in a way that depends on the health of the pristine Western Slope watershed and the gold medal fishing it offers.

The gold medal fishing and unique species of fish that call the waters home is a huge source of tourism to Garfield County — but was in jeopardy earlier this year.

According to the USGS monitor near Dotsero, the average temperature of the river was increasing too quickly in late March, and without releases from Green Mountain Reservoir, the river could have heated up too quickly. On March 28, the river was recorded at 52.3°F, nearly 10 degrees hotter than the 10 year median. A similar trend continued into summer — the river was recorded at 69.4°F on July 5, again almost 10 degrees hotter than the median.

Harcourt was shocked that the Colorado Parks and Wildlife didn’t put a fishing ban on the Colorado River through the warm river temperatures, and thought it could even creep into trips on the Roaring Fork.

“The river got extremely warm about a month ago. I was expecting them to close the Colorado, and was almost thinking they were going to close the Fork for the first time ever,” Harcourt explained. “They started releasing some water out of the Frying Pan, and that really helped on the Fork, and they’ve been releasing water out of Green Mountain which has been helping the Colorado.”

He continued to explain that he could remember previous years in which the Colorado was closed — but wasn’t worried about having to adapt if it happened.

“I can remember three years where they’ve closed the Colorado River before, and I could have sworn it would happen this year. Amazingly it didn’t and the river was able to stay cool due to some dam releases.”

According to the Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW), the river didn’t reach the threshold for temperature nor flows to close the river. The last time the Colorado River was closed was in 2022 due to high water temperatures.

“When water temperatures reach 71° F or above, it becomes difficult for fish to survive, even when practicing catch and release,” the agency states. “River temperatures are monitored throughout Colorado’s rivers using temperature loggers. This data, in addition to other factors such as low flows and high fishing pressures, are used to determine the need for voluntary fishing closures.”

The health of the Western Slope watershed is vital to everything from sustaining basic living needs to economic growth and more. But even as the Colorado River is bound to be crucial to the Western Slope and other states for years to come, what that future looks like is more uncertain than ever.

“There is a lot of summer left, and this is where the rains would really help ease those demands — but again, that’s something that we just aren’t seeing and it is contributing to the extreme drought conditions right now,” Langenhuizen said.

Roaring Fork Valley nonprofit wants to expand scholarships for those on autism spectrum

Ascendigo Autism Services is launching an “Adventure for All” fundraising campaign, an initiative aiming to expand access to outdoor adventure programs for youth and adults on the autism spectrum.

Carbondale paraglider breaks continental distance record

Imagine descending from nearly 18,000 feet on a down draft at 1,000 feet per minute, or being shot away from earth at twice that speed.

Support Local Journalism

Support Local Journalism

Readers around Glenwood Springs and Garfield County make the Post Independent’s work possible. Your financial contribution supports our efforts to deliver quality, locally relevant journalism.

Now more than ever, your support is critical to help us keep our community informed about the evolving coronavirus pandemic and the impact it is having locally. Every contribution, however large or small, will make a difference.

Each donation will be used exclusively for the development and creation of increased news coverage.