What is the risk of plague on Colorado’s Western Slope?

Hint: It ‘isn’t zero’

Madison Rahhal/Vail Daily archive

While medical treatment and sanitary improvements have lessened its impact, the bubonic plague — responsible for the Black Death in the 14th century — could still be alive in your backyard.

Early in August, Jefferson County Public Health reported that a domestic cat contracted the plague in Evergreen and later died. While it was Colorado’s first case this year and cases are rare, pets and even humans can contract the disease.

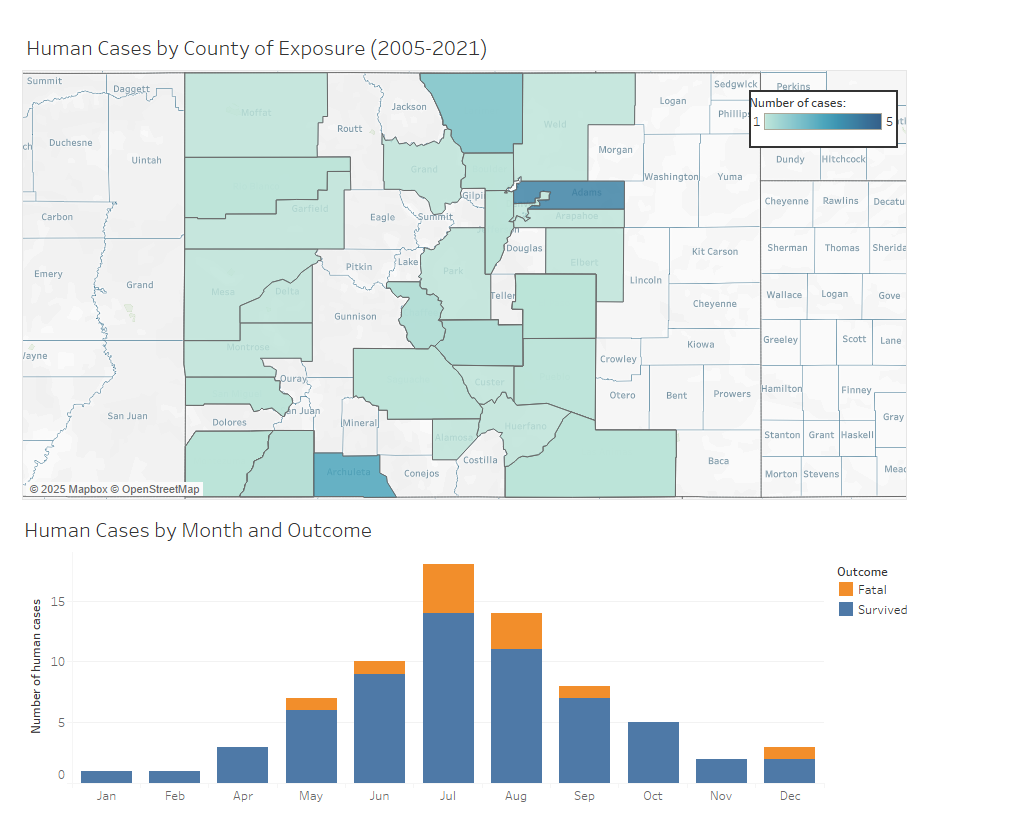

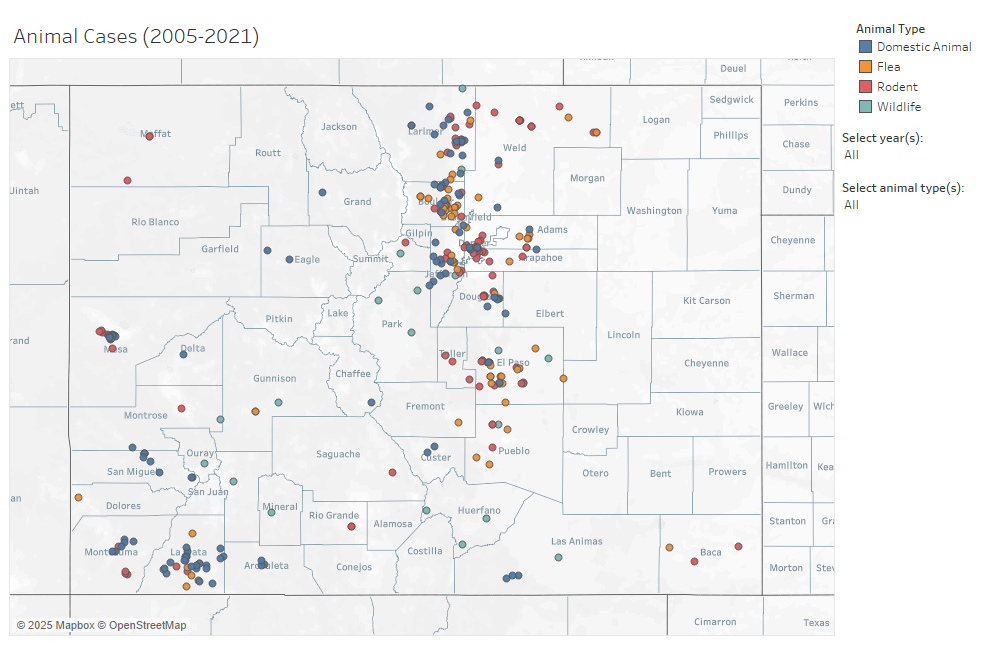

According to the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, there were 431 confirmed animal cases of the plague in Colorado between 2005 and 2021. During the same 16-year period, there were 60 human cases, 11 of which were fatal.

“Plague is persistent in the western United States, including Colorado,” said Heath Harmon, director of Eagle County Public Health & Environment. “It’s rare in both animals and even more rare in humans, but the risk isn’t zero.”

What is the plague and where does it come from?

Simply put, the plague is a bacterial infection.

It has a few presentations. The most common is bubonic, presenting with “buboes,” or swollen, painful lymph nodes. There is also pneumonic plague, a serious and potentially fatal type with infection hitting the respiratory system. While rare and highly fatal, there is also septicemic plague, which occurs when the bacteria infects your bloodstream.

Plague symptoms can be a bit challenging because they sound a bit like everything, said Carly Senst, Pitkin County Public Health epidemiologist.

This includes severe fever, headaches, chills and, with bubonic plague, buboes.

Cases typically peak in the state’s warmer months, according to the state’s data from 2005 to 2021.

However, because cases are rare, suspecting plague comes down to tracking possible detection and infection in your area.

Plague is passed along through the bite of an infected flea. While it can be passed to other animals and humans through fleas, the most common carriers are previously-bitten rodents.

In Colorado, prairie dogs are the top concern, but plague can be present in any rodent, including ground squirrels, chipmunks, rats, mice and rabbits.

While Colorado Parks and Wildlife primarily monitors for plague in prairie dogs, it does occasionally test other species that show signs of the disease.

Often, when infected, the plague can kill rodents in large numbers, so reporting widespread die-offs to the state wildlife agency can help with detection, Senst said.

With humans, direct infection from fleas or rodents is possible, and so is contracting it from pets.

“A lot of times, we’ll see the fleas get on to pets and then go from pets to the people,” said Dan Hendershott, the environmental health manager for Summit County Public Health.

“We actually do see it quite often in domestic cats that are going to be roaming outside,” Harmon said. “They might be likely to come into contact with an infected rodent or come into an area where there are wild rodents and come into contact with the fleas directly.”

Similarly, dogs could come into contact with infected fleas or rodents.

“You let your dogs roam around, they acquire the fleas, and then you sleep with your dog on your bed. The flea jumps onto you, bites you, and you can get the plague,” Hendershott said.

But since the 14th century pandemic, both detecting and treating plague have become easier.

“If somebody comes down with a pretty severe bacterial infection, at the physician’s office, this is something that they will test for, especially if there is known exposure to hypothetical or potential plague areas,” Senst said.

“It sounds kind of dramatic to say that the plague is present, but it is readily treatable with antibiotics,” she added.

The timing of treatment, however, is critical.

“It can cause a pretty severe disease, whether that’s in animals or in humans, so early treatment is incredibly important,” Harmon said.

How to avoid the plague, like the plague

Luckily, since the days of the Black Death — which killed millions of people in Europe — human hygiene has improved greatly and is a primary reason that the risk of plague has dropped significantly.

“We have better protections against rodents in our homes. We have better protections against fleas in our homes, and so humans are a lot less likely to be infected with fleas, which is great news for many different reasons,” Senst said.

However, as Harmon noted, plague is persistent, so the risk is “never zero,” and there are things you can do to further reduce that risk.

The best thing you can do is “be mindful of your outdoor pets, utilizing those flea and tick preventions, even in high elevation areas,” Senst said.

“Be mindful of keeping dogs on leash, be aware of outdoor cats, and the fact that they do have a risk not only for their environment, but also the risk of bringing illness back into the home,” Senst said, adding that flea and tick medications are the “best way to eliminate the risk of those fleas coming in from those rodents and hopping a ride on your pet.”

Additionally, humans can reduce their risk — not only of plague but other animal-borne diseases — by avoiding sick or dead animals, closing areas where rodents can enter homes, cleaning rodent droppings with a bleach solution, removing clutter from both inside and outside of your home and reporting possible interactions and exposure to public health departments.

Also, because early treatment is important for plague, if humans come into contact with rodents or get flea bites, monitoring for symptoms is also critical to mitigating risk.

Understanding the risk of plague and other animal-borne illnesses on the Western Slope

In higher elevation areas, plague is even more uncommon.

“As our ecosystem shifts down in the plains to lower elevations, higher temperatures, there’s typically higher population densities of potential plague-carrying rodents,” Senst said. “Up at elevation, our populations are a little bit more diversified or broken up. We don’t have massive acres of ground squirrels that can cause perfect breeding grounds for those fleas. We’re separated by mountains. We have colder temperatures.”

Within the central mountain region, most of the counties have not had animal or human cases between 2005 and 2021, according to the Colorado health department. There were two animal cases in Eagle County and one in Grand County. Grand and Garfield counties each had one human case during that period.

“We don’t necessarily see it as commonly in some of our higher mountain counties,” Harmon said. “There are fewer chances of coming into contact with infected animals or fleas up here.”

Eagle County’s most recent case was in a domestic cat in 2023, Harmon said.

With numbers low, High Country public health departments are typically more concerned with other animal-borne, or zoonotic, illnesses.

“What we’re looking at predominantly in Pitkin County, as far as that kind of higher elevation county, is we get a lot more rabies than we would plague,” Senst said.

Rabies, commonly carried by bats in the High Country, is followed by West Nile, carried by mosquitoes, and then tick-borne illnesses, which have a similar risk level as plague, Senst said.

Eagle, Summit and Pitkin counties have both had confirmed rabies cases in bats this year.

“We want people to call us if they were bit by an animal or their pet had an exposure to a wild animal, so that we can kind of assess the situation because rabies is (nearly) 100% fatal,” Hendershott said, adding only two people have ever survived it once contracted.

West Nile has been detected in six Colorado counties this year, including Garfield County.

While Summit County hasn’t had a case of it, it is also tracking hantavirus, which is found in deer mice, and has been reported in nearby counties, Hendershott said.

“Colorado has the second-most cases of hantavirus,” he added, citing the Centers for Disease Control data.

Part of the risk comes down to the likelihood of contraction.

“The severity of the disease is greater with plague compared to West Nile virus, but the risk of actually being infected with plague compared to West Nile virus is going to be much less,” Harmon said.

Similar to the plague, avoiding these zoonotic illnesses comes down to avoiding contact with animal carriers, understanding symptoms, seeking vaccinations and treatment, and reporting anything concerning.

Support Local Journalism

Support Local Journalism

Readers around Glenwood Springs and Garfield County make the Post Independent’s work possible. Your financial contribution supports our efforts to deliver quality, locally relevant journalism.

Now more than ever, your support is critical to help us keep our community informed about the evolving coronavirus pandemic and the impact it is having locally. Every contribution, however large or small, will make a difference.

Each donation will be used exclusively for the development and creation of increased news coverage.