Disney’s deep Colorado history runs through Vail, Aspen

State's historic newspaper archive allows company's Rocky Mountain story to be rediscovered

Vail Trail/Vail Daily archive

Sixty-five years ago, as Colorado was buzzing over the debut of the state’s largest bowling alley, a visit from the venue’s owner, Walt Disney himself, suggested the company’s real interest in Colorado might lie beyond the Continental Divide.

It’s an era of outdoor recreation history that has long intrigued Coloradans, though much of Disney’s interest in the Rocky Mountains has faded from public memory. Thanks to the recent digitization of a wide range of historical newspapers by History Colorado, however, that history is easier than ever to explore.

Through coloradohistoricalnewspapers.com — which includes free archives of the Vail Trail, the Aspen Times, and the Rocky Mountain News — it’s now possible to follow the Disney corporation’s 35-year footprint in Colorado, from the Denver bowling alley project in the 1960s to the company’s plans for a major development at the base of Beaver Creek in the 1990s.

The 80-lane bowling area, Olympic-sized pool and go-kart track known as the Celebrity Sports Center was co-owned by a group of Hollywood elites who had been making regular visits to the state since the project broke ground in 1959.

“Months of research by highly specialized people have shown us that this is one of the fastest growing areas in the United States,” Disney said during a 1959 visit to Denver. “We had other cities under surveillance, but Denver was an overwhelming choice.”

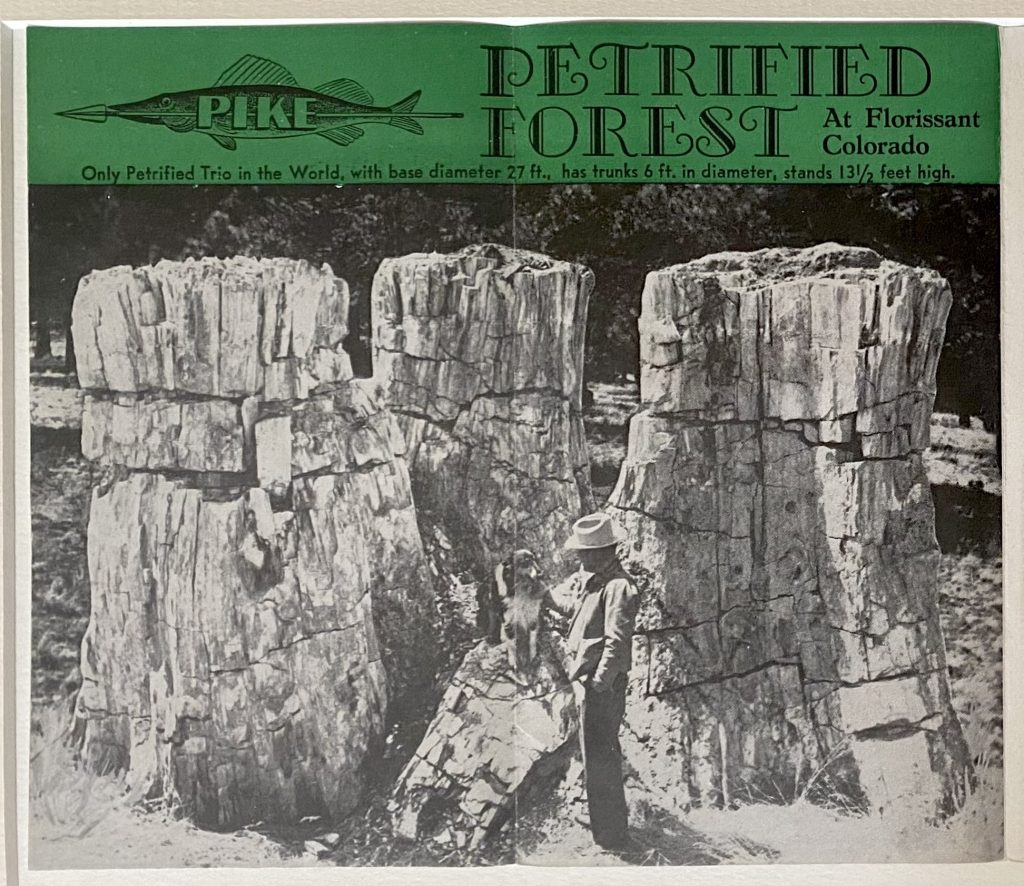

It was being called Disney’s first business venture in Colorado, but that wasn’t exactly true. A few years earlier, in 1956, Disney had visited the Pike Petrified Forest and completed a deal with Colorado Springs resident Jack Baker to buy (and have shipped to Disneyland, where it remains today) a 5-ton petrified redwood tree from Baker’s land, the site of the modern-day Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument.

By the 1960s, as his bowling alley was opening, Disney was likely interested in another business in Colorado, as well — the ski business. The emerging ski towns of Vail and Aspen received visits from Disney as he looked into new possibilities for his recreation empire.

Disney struck up a friendship with the legendary University of Denver Ski Team coach Willy Schaeffler, who was director of ski events at the 1960 Squaw Valley Olympics, where Disney had been in charge of pageantry. Disney had been interested in skiing since the 1930s, when he provided a few thousand dollars of startup capital for the Sugar Bowl ski area in California, and long dreamed of opening a ski resort of his own. Following the conclusion of the Olympics, Disney got serious about the idea, hiring Schaeffler to join his team of resort developers.

Aspen learnings applied in Florida

At some point in the 1950s, Disney had seen Aspen Ski School Director Fred Iselin’s film “Little Skier’s Big Day,” which was filmed in Aspen by Bob Murri and starred 5-year-old Susie Wirth, also of Aspen. Disney bought the film and adapted it into “Fantasy on Skis,” which aired on Disney’s “Wonderful World of Color” television series to an audience of 40 million people on Feb. 4, 1962.

Later that year, Disney visited the Celebrity Sports Center and then took a cruise west on Highway 6, stopping in Vail on his way to Aspen. Vail pioneer Rod Slifer, who died in 2024, was also in the Vail area at the time and recalled Disney’s September 1962 visit in a 2020 interview.

“(Pete Siebert) wanted to run by Walt Disney to get some advice on building a ski area and that sort of thing, and wondered if Disney would have any interest in participating in some way, maybe be on the board,” Slifer said.

But Willy Schaeffler had also been scouting a few ski areas for Disney, and wasn’t hot on Vail. A Sports Illustrated article, published in 1962, quoted Schaeffler saying, “Vail has the vertical drop — 2,700 feet — but I’m not sure it has the steepness, the sharp concave terrain features that challenge really fine skiers. The better runs may be there somewhere, but I haven’t seen them yet.”

Schaeffler’s assessment likely helped convince Disney not to get involved in Vail, as Schaeffler was a trusted advisor.

By the end of 1962, the Disney corporation had bought out the other celebrities at the Celebrity Sports Center, becoming the sole owner. At the Denver recreation complex, the company could be seen developing some of the tools it would later use at its Florida project, including cast member-training techniques and exhibitions like Goofy waterskiing behind a boat (a regular attraction at the Celebrity pool).

But one of the biggest learnings Disney would bring from Colorado to Florida came in the form of a land speculation deal that blew up on Walt when the owners realized it was he who was attempting to purchase the land.

Disney was fond of Aspen, visiting for nearly a month in the winter of 1963. His visit was covered by the Aspen Times Weekly, which wrote in the Feb. 15, 1963 edition, “Local pilots have been ogling the beautiful Beechcraft ‘Queenaire’ which arrived at the Aspen Airport last Saturday bringing Mr. Walt Disney to town for about a month’s stay.”

Disney was close to purchasing 2,200 acres of land outside of Aspen, but “the deal suddenly fell through because the seller raised his asking price,” Disney biographer Neal Gabler wrote in “Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination.”

The seller had likely learned — possibly from the Aspen Times’ coverage of Disney’s visit — that he had a high-profile buyer with deep pockets, and raised his price. It was a valuable lesson for Disney, who would not make the same mistake twice.

Later, when attempting to purchase the land that would later become Walt Disney World in Florida, Disney acted more clandestinely, leaving his sellers unaware that he was the buyer.

Legendary meeting in Vail

As his company was buying up land in Florida, Disney and Schaeffler had also settled on the Mineral King Valley in California for Disney’s ski resort project, purchasing land there, as well. Disney had become a major proponent of outdoor recreation by the 1960s, saying during a public service announcement which aired on television in 1966, “As an American you have an interest in all public lands … to receive the greatest benefit from these public lands, you should request that they be managed to include all forms of outdoor recreation.”

But Disney had already developed terminal lung cancer by the time he recorded that message, and he was dead by the end of 1966. His company tried to maintain his commitment to creating the Mineral King ski area throughout the 1970s, but was unsuccessful. In 1977, the Walt Disney Company was in negotiations to purchase the Sun Valley ski resort in Idaho, but that deal fell through, as well.

In the 1980s, the legendary Disney leadership duo of Michael Eisner and Frank Wells, who led the company’s creative and financial renaissance, began in Vail. It was a meeting so impactful that Eisner wrote about it in the very first sentence of his book “Work in Progress.” That sentence reads: “Frank Wells was fifty years old when our paths crossed on the ski slopes of Vail, Colorado, in the spring of 1982.”

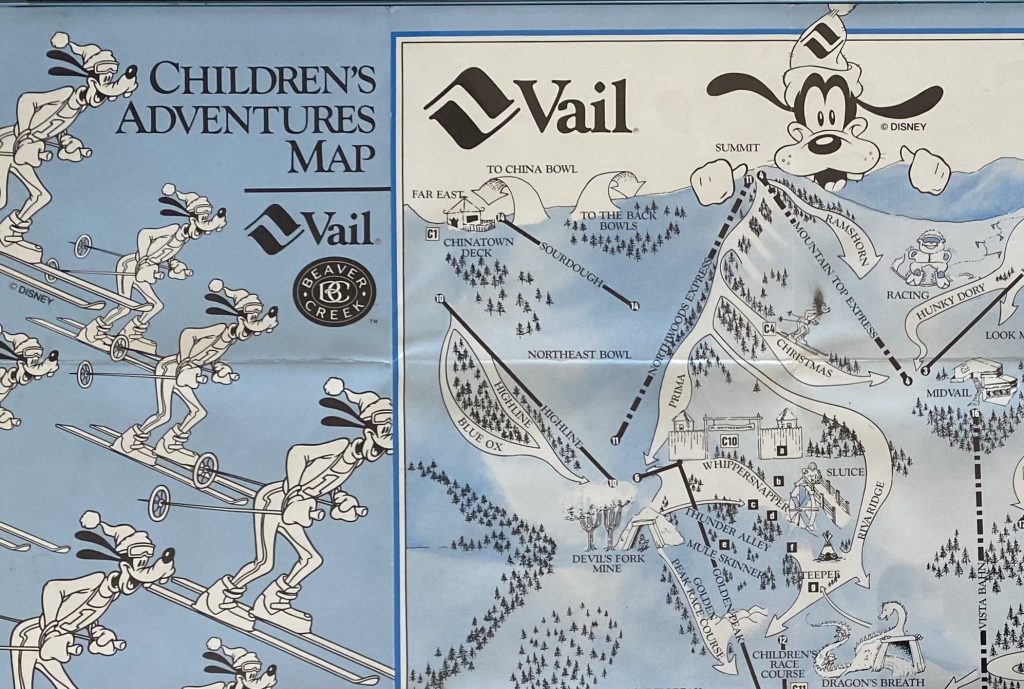

Wells, who owned a residence in Vail, later helped usher in a Vail-Disney partnership, as Vail signed a licensing agreement with Disney in 1986 to use Disney’s Sport Goofy character to promote children’s skiing. The announcement came just two weeks after Vail and Disney had announced another partnership where Disneyland would be used as a venue to promote Vail vacations. Disney awarded 25 free trips to Vail per day at the park every day from Nov. 28 to Dec. 19, 1986.

Wells was quoted in the Vail’s Trail’s coverage of the deal.

“We think Sport Goofy is especially appropriate because he aspires the average weekend athlete to get involved solely for the fun of it,” Wells said.

Vail local Brian Hall, who had been hired to stage children’s theater plays in the plaza at Beaver Creek at the time, said Disney provided the costume and invited him to attend mascot school at Disneyland, where, after shadowing Mickey and Minnie, they suited up themselves and made the rounds of the park,” according to a 2014 Vail/Beaver Creek Magazine story. “Hall and crew returned to apply some Magic Kingdom magic to the slopes of Vail and Beaver Creek.”

The magazine also recounted Hall’s version of how the partnership began.

“As the story goes, (Gillette and Wells) rode up the chairlift and decided, ‘We’ve got to do something together,'” Hall said. “What they came up with was Sport Goofy.”

Kids who attended children’s ski school at Vail were outfitted with Mickey Mouse-branded skis from K2, and a theme park atmosphere was created on the mountain.

“Children ski through a magical forest with talking animals near Gitchegumee Gulch, through Indian Burial Grounds, through the gates of old West Ft. Whippersnapper and down a re-created mine shaft at Devil`s Fork Mine,” the Chicago Tribune reported in 1989. “Meanwhile, later at neighboring Beaver Creek 12 miles away, Sport Goofy can be seen again skiing with children on a run that includes a visit to see a hibernating bear in a cave and through tepees in an Indian village.”

Vail and Beaver Creek made Disney-themed trail maps to coincide with these adventures, depicting Sport Goofy skiing around in the kids’ areas. Those zones where Sport Goofy was seen skiing turned out to have a much longer-enduring legacy than the character himself; today, you can still ski through features like the sleeping bear cave.

The Sport Goofy deal lasted until 1994, and while it was expiring, another Vail-Disney partnership was budding. In early 1995, Vail Associates announced that a Disney development was slated to be an integral part of the $75 million Village Center at Beaver Creek.

East West Partners and Vail Associates, development partners in the Beaver Creek Village Center project, knew that Disney was looking to expand its Vacation Clubs into ski resorts and convinced Disney that Beaver Creek was a prime choice.

“This has zero to do with the theme parks,” East West Partners’ president Harry Frampton told the Vail Trail in 1995. “I don’t think the buildings will look significantly different from the other buildings in Beaver Creek.”

But the Beaver Creek metro district’s planning board wanted more control than the Disney developers were willing to offer, and Disney sold the plans to another corporation, Hyatt. The Hyatt corporation then brought Disney’s ideas — which included a performing arts center with an ice rink on top of it — to fruition at Beaver Creek.

“Construction of the $75-million Village Center, including a performing arts center and ice rink, will go ahead despite Disney’s withdrawal,” the Associated Press reported in 1995.

In that story, East West Partners spokesman Ross Bowker described the situation using an analogy well suited to Vail and Disney — that of a family.

“Disney and Vail Associates worked very hard to get this project together,” Bowker said. “They decided not to get married, not that they didn’t like each other.”

But the headline that’s probably the most memorable from the affair stated otherwise. It came from the Aspen Daily News in November of 1995:

“The mouse doesn’t like the beaver.”

Support Local Journalism

Support Local Journalism

Readers around Glenwood Springs and Garfield County make the Post Independent’s work possible. Your financial contribution supports our efforts to deliver quality, locally relevant journalism.

Now more than ever, your support is critical to help us keep our community informed about the evolving coronavirus pandemic and the impact it is having locally. Every contribution, however large or small, will make a difference.

Each donation will be used exclusively for the development and creation of increased news coverage.